Why Does God Allow Evil?

Rev. Mark Schaefer

Cheltenham United Methodist Church

May 3, 2020

1 Peter 2:19–25; John 10:1–10

I. BEGINNING

Some years ago, I took a sabbatical to work on a book. During that sabbatical leave I planned on worshiping with a different house of worship every weekend. On my second weekend, I went to St. Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral in D.C. where my friend and colleague Fr. Dimitri Lee was serving.

That day was September 13 and he noted that it was a Sunday that lay between September 11 and the elevation of the Holy Cross on September 14. He said it was a Sunday that lay between two days of great tragedy and violence. Between two days that raised questions like: Why do the innocent suffer? Why does such tragedy happen? Why does God allow evil? And he said, “A perfectly good answer to those questions is, ‘I don’t know.’” And then he left it at that.

I was astonished. Only the Orthodox, with their embracing of mystery, could pose the great question of theodicy—of the justice of God—and be content to leave it unanswered.

No Protestant would have done that, that’s for sure. Most of us would try to answer.

So, as a Protestant minister preaching this sermon, why does God allow evil?

Well, I don’t know, either. To tell you the truth.

I have an idea—but I don’t know. Not for sure.

Image courtesy Wordle

This is a question that has vexed theologians and philosophers for centuries. It would be hubristic of me to say that I had the answer for this most difficult of questions: why is there evil? Where did it come from? Why does God allow it to exist? Why do the innocent suffer? Why is there injustice in the world? Oppression and violence? It is known as the question of “theodicy.” Quite frankly, answering these questions is above my pay grade.

Still, as with all good questions, there is virtue in asking it. For a questioning faith is a living faith. When your faith has run out of questions, it becomes not faith but dogma. Not true religion, but merely a code of behaviors and a rigid set of understandings. No, for us, we ask the unanswerable questions precisely because that is a vital part of our faith. And while there are no easy answers, it’s not really about the answers, it’s about having the safe space to ask the questions.

Read more...

Is the Resurrection Real?

Rev. Mark Schaefer

April 26, 2020

Acts 2:14, 36–41, Luke 24:13–35

I. BEGINNING

When I was in seminary, I had the privilege of studying under a wonderful New Testament scholar, and current Dean of Perkins Theological Seminary, Craig Hill. Dean Hill is an excellent scholar, having written a wonderful book about conflict in the early church called Hellenists and Hebrews and a fantastic book on Christian end-times theology called In God’s Time. (Craig, if you’re watching, you can either Venmo me the endorsement money or just mail me a check.)

The Road to Emmaus by Ducio di Buoninsegna

When he was getting his doctorate, he had the privilege of studying with one of the great scholars of our age, E.P. Sanders, author of the landmark book Jesus and Judaism, which established the gold standard for historical Jesus studies in the late Twentieth Century. I had occasion to hear Dr. Sanders speak at Wesley seminary and there are things he said in his remarks that to this day stick with me. I’ve had occasion to read Jesus and Judaism as well as a few other books by Sanders and am impressed by the depth of his scholarship and his intellect.

As a scholar of the historical Jesus, Sanders was engaged in the exploration of the gospels to determine what facts, if any, could be defended from an objective, historical point of view. That is, what are the things from Jesus’ story that a disinterested, secular historian could affirm as accurate and credible? Sanders had fashioned a list of “several facts about Jesus’ career and its aftermath which can be known beyond doubt.”[1] They are:

- Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist

- Jesus was a Galilean who preached and healed.

- Jesus called disciples and spoke of there being twelve.

- Jesus confined his activity to Israel.

- Jesus engaged in a controversy about the temple.

- Jesus was crucified outside Jerusalem by the Roman authorities.

- After his death, Jesus’ followers continued as an identifiable movement.

- At least some Jews persecuted at least parts of the new movement, and it appears that this persecution endured at least to a time near the end of Paul’s career.

Noticeably missing from this list is Jesus’ resurrection. My professor told me that he had wondered why Sanders couldn’t add that to the list, since it was attested in every single gospel, in the epistles, including the writings of Paul who declared that he had seen the risen Christ. Surely, that was just as attested as his baptism by John, wasn’t it? Why could his mentor and friend not make that leap?

“Because that kind of thing just doesn’t happen,” was the response.

If we’re honest we admit he’s not the only one. Our pews and often our pulpits are full of people who sing the hymns and celebrate the stories of Easter, but who wonder deep down: is this real? Did Jesus really rise from the dead? And if so, in what way?

Read more...

Am I Lost If I Have Doubt?

Rev. Mark Schaefer

Cheltenham United Methodist Church

April 19, 2020

John 20:19-31

I. BEGINNING

If you’re going to get a place in history, be sure you get a good epithet to accompany your name. Like “the Great”, if you can swing it. King Alfred the Great—the only “the Great” in all of English history—earned that distinction likely for his promotion of Anglo-Saxon literature. Pope Gregory the Great earned that epithet for his guidance of the church into the post-Imperial world and his presiding over the collection of the Gregorian Sacramentary and Gregorian Chant.

You’ll want to aim high, of course, and go for epithets like “the Conqueror” or “the Magnificent” or “the Powerful”. And if they called you “the Fair” or “the Just” or “the Merciful” that wouldn’t be bad either.

Of course there are other epithets you could earn like “Pepin the Short”, “Charles the Bald”, or “John the Theologian.” Those are mostly harmless. But definitely try to avoid ones like “the Accursed”, “the Impaler,” or “the Apostate.” You wouldn’t want to go through life with an epithet like that hanging over you.

Which is why I always feel so bad for poor Thomas. Thomas the Doubter. Doubting Thomas. That’s a rough nickname to live down, especially in church, right?

Read more...

The Promised Land

Rev. Mark Schaefer

April 12, 2020—Easter Sunday

Acts 10:34-43; Matthew 28:1–10

I. BEGINNING

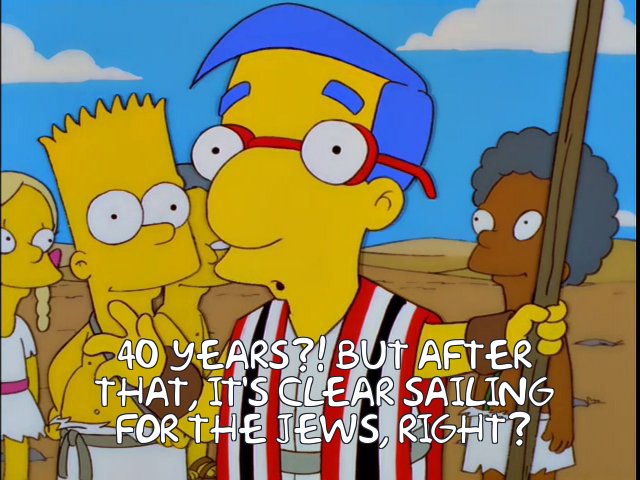

A number of years ago, The Simpsons had a special in which the Simpsons characters related a number of classic Bible stories. The stories included things like the Garden of Eden and King Solomon’s wisdom, wherein Homer Simpson played King Solomon deciding who was the true owner of a pie claimed by two men. (Homer’s decision: “The pie will be cut in half. The two men will be killed and I will eat the pie.”)

But the scene that sticks out in my mind today was their reenactment of the Exodus from Egypt. Nerdy kid Milhouse Van Houten plays Moses and in one particular scene after the deliverance through the Red Sea and the revelation of the Law asks Lisa Simpson to check the Biblical text she has:

“So, Lisa, what’s next for the Israelites? Land of milk and honey?”

“Hmm, well, actually it looks like we’re in for 40 years of wandering the desert.”

“40 years?! But after that, it’s clear sailing for the Jews, right?”

“Umm, more or less… hey, is that manna?”

And the reason this particular scene occurs to me is that it reminds me a little of how I feel about Easter.

That seems like a strange thing to say, I grant you. After all, this is Easter Sunday. We’ve made it through all the trouble. The long wilderness of Lent and the suffering and sorrow of Holy Week have yielded to the Promised Land of Easter. Christ is Risen and everything’s wonderful.

Why wouldn’t there be clear sailing? Why wouldn’t the arrival in the promised land be the happy ending to the story?

Read more...

To Crucify the King

Rev. Mark Schaefer

April 10, 2020—Good Friday

John 9:9-16a

I. INTRODUCTION

John’s Gospel is full of irony. It often has people saying things that have double meanings that they did not intend. The high priest says, “It is better for you to have one man die for the people than for the entire nation to be destroyed.” He thinks he’s making a calculated political decision about life under occupation, but the reader understands it as a statement of Jesus’ atoning death for the whole world.

But nowhere is the irony pitched higher than in the stories of Good Friday. Jesus is brought before Pontius Pilate, with whom he has a very enigmatic and double-meaning laden conversation about kingship and power. He presents Jesus to the crowds, saying “Here is your king!” They shout out “Away with him! Away with him! Crucify him!” He asks them, “Shall I crucify your king?” And the chief priests answer, “We have no king but the emperor.”

And here is the irony: in the Jewish Avinu Malkeinu prayer are the words “We have no king but you (God).” And here we have the high priests saying, “We have no king but Caesar.” The irony is that these words are spoken by people who should know better—people familiar on a direct level with what their faith requires. A faith that declares that God is King, a faith that seeks to live out righteousness and justice as a way of demonstrating loyalty and fidelity to that king. How could people steeped in their faith claim loyalty to the worldly power of the Emperor of Rome, a power that stands for tyranny, injustice, and oppression? That stands against the poor and the lowly?

But is it really any different with us?

Read more...

If You Know These Things

Rev. Mark Schaefer

April 9, 2020—Maundy Thursday

John 13:1-17, 31b-35

I. BEGINNING

If any of you has ever traveled to England or become familiar with English place names, you’ve no doubt become aware that the English have a long history of wearing down their words to where their pronunciations and their spellings seem to have little to do with one another. A word spelled Featherstonehaugh is pronounced “Fanshaw.” Cholmondely is pronounced “Chumlee.” Wriothesley is pronounced “Roxlee.”

Which is how we wind up with Maundy Thursday. Long ago it was known as Mandatum Thursday, from the Latin word for “commandment.” The Thursday in Holy Week is so called because it is on this Thursday that we read the story of Jesus giving to the disciples a “new commandment”: that we love one another as he has loved us.

Jesus makes a very interesting observation when he speaks to the disciples. He says, “You call me your lord and teacher, and you are right, because that is what I am.” But then he goes on to describe what that means. What it means to call Jesus Lord and teacher. In the Gospel of Matthew a very similar statement that “Not everyone who calls me ‘Lord, Lord’ will see the Kingdom of Heaven but only those who do the will of my Father.” Here Jesus is making a connection between what it means to be saying “Lord,” and what it means to do the commandments of God and to live lives of faith.

This all takes place in the context of the story of Jesus washing the feet of his disciples. There is no more humbling act in the ancient world than that of washing the feet of another person. It’s what servants do. It’s what household slaves do. In John’s gospel, Jesus is many things. He is the Son of God, the Messiah and God’s agent in the world. In the very beginning of John’s gospel, we read, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” And that the Word takes on our flesh and becomes a human being. What then does it mean that the Word of God in flesh, the Son of the Living God, should reach out in humility, should wash the feet of the one who would betray him? What does that mean for us, who proclaim Christ to be our Lord and our Teacher? If it does not mean that we turn around and we go back into the world as servants, in humility, in compassion, if it does not mean that we wash others’ feet metaphorically, perhaps even literally, if it does not mean that we are willing to serve one another, that we are willing to take on the burden that Christ bore for the sake of others, then what does it mean when we say that Christ is our Lord and Teacher?

Read more...

The Wilderness of Betrayal

Rev. Mark Schaefer

April 5, 2020

Isaiah 50:4–9; Matthew 26:47–75

I. BEGINNING

If done right, Palm Sunday would be an awkward Sunday. Palm Sunday isn’t usually perceived in that way and that’s because Palm Sunday is often done wrong.

Palm Sunday, the day we commemorate Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The culmination of a preaching ministry throughout Galilee: a year of teaching, healing, witnessing, and transforming. A year of bringing to so many people a sense that the Kingdom of God was at hand. A year in which expectations were so high that things were going to change decisively for ordinary people.

A Sunday, which unlike for us today, was not a day of rest, but as the first day of the week was a day of activity and excitement. A day to begin the week during which the great Passover holiday would take place, a holiday celebrating freedom from slavery and oppression and God’s liberating power. A Sunday in which all the hopes and dreams of so many are placed upon this one remarkable man—Jesus of Nazareth, whom some dare to hope is the long-awaited messiah, the deliverer-king who will free the people from their oppression under the Roman Empire.

And so as Jesus rides into Jerusalem, he makes conscious use of a prophetic symbol, riding in humbly on a colt. The people throw down their cloaks in his path and cut leafy branches in the fields and shout “Hosanna!” It’s a festive scene.

And so we in the church are fond of re-creating this scene. We sing hymns with hosannas in them. We hand out palms. We wave them a bit. We decorate the sanctuary with palm branches. It’s all very festive and wonderful. It doesn’t seem awkward at all.

But that’s probably because we’re doing it wrong.

See, we are aware of how this story ends. We know that in a few days’ time, the crowds—the same crowds—will be shouting not “Hosanna to the Son of David!” but “Crucify him!” Is there any reason not to greet this story with embarrassment for how we know the story turns out?

This story ought to elicit the same gulps we get when we see Anakin Skywalker meet Obi Wan Kenobi for the first time and realize: this nascent friendship is doomed to end in pain, tragedy, and death. We ought to have the same feelings when we get when we watch the hero meet the character that we, as the viewers, know will be the hero’s undoing, but the hero does not. It should be hard for us to celebrate Palm Sunday without a sense that things are about to go very, very wrong for Jesus.

Now, there are churches (and many Christians) who simply go from Palm Sunday right to Easter. And I suppose it’s easy to go from “Hosanna” to “Alleluia!” that way. But not if you do it right.

For a recognition of the power of this story is a recognition that at the heart of it there is a tremendous tragedy. A tragic turn of events in which shouts of praise turn to shouts of condemnation and death. If we, as the church, do it right, we cannot be all smiles and pretend that this story does not start in a promising fashion and yield to a bitter conclusion. We cannot face the adulation of Palm Sunday without facing the reality that this story ends in betrayal.

II. THE BETRAYAL OF JESUS

And betrayal is at the heart of this story. There are the obvious betrayals: Judas betrays Jesus’ location to the temple priesthood; Peter denies even knowing Jesus. The crowds that shout “Hosanna!” on Sunday are shouting “Crucify him!” on Friday. The disciples who are scattered on Thursday night, are nowhere to be seen on Friday and Saturday, and are found to be in hiding on Sunday. The leaders of the people, who ought to be protecting the innocent, instead hand over an innocent to the occupying power that will execute him. There are so many betrayals at the heart of this story that it typifies the kind of tragic drama that we know so well.

III. OUR BETRAYALS

There is something about betrayal that goes right to the heart of us. It is impossible to betray someone with whom you are not already close or with whom you do not have an intimate relationship. We value faithfulness and loyalty in our relationships. It’s what makes them work. But in order to foster relationships, we need to take leaps of trust. We make ourselves vulnerable to one another. And betrayal cuts right at the heart of that. We cannot be betrayed by one we have not first made ourselves vulnerable to.

The word “fidelity” is based on the word for faith. Loyalty, then, is not just a personal virtue, it is at the heart of faith. When we experience betrayal, it is not just an interpersonal infraction; it is a crisis of faith. When one has been betrayed by someone trusted, it becomes hard to have faith in anything.

There can be fewer experiences of raw pain than the realization that one whom you had trusted has betrayed that trust. When we are the victims of betrayal, we find ourselves in a wilderness place. We might wonder how God is known when we have experienced betrayal?

In the gospel story, we see tremendous betrayal. By Judas, by Peter, the disciples, the crowds, the leadership. Even at one point, Jesus wonders if God has betrayed him, too.

But again, we know this story’s ending. We know that it does not end with the jeering crowds, or the denying followers, or the traitorous friend. We know that it ends with new life. With hope. With the in-breaking of the Kingdom of God. Given that, we have to realize that God must be at work even in the midst of betrayal.

IV. FIDELITY IN BETRAYAL

Some have argued that betrayal can itself be an act of faith.

The Texts

Isaiah 50:4–9 • The Lord God has given me the tongue of a teacher, that I may know how to sustain the weary with a word. Morning by morning he wakens— wakens my ear to listen as those who are taught. The Lord God has opened my ear, and I was not rebellious, I did not turn backward. I gave my back to those who struck me, and my cheeks to those who pulled out the beard; I did not hide my face from insult and spitting.

The Lord God helps me; therefore I have not been disgraced; therefore I have set my face like flint, and I know that I shall not be put to shame; he who vindicates me is near. Who will contend with me? Let us stand up together. Who are my adversaries? Let them confront me. It is the Lord God who helps me; who will declare me guilty?

Matthew 26:47–75 • While he was still speaking, Judas, one of the twelve, arrived; with him was a large crowd with swords and clubs, from the chief priests and the elders of the people. Now the betrayer had given them a sign, saying, “The one I will kiss is the man; arrest him.” At once he came up to Jesus and said, “Greetings, Rabbi!” and kissed him. Jesus said to him, “Friend, do what you are here to do.” Then they came and laid hands on Jesus and arrested him. Suddenly, one of those with Jesus put his hand on his sword, drew it, and struck the slave of the high priest, cutting off his ear. Then Jesus said to him, “Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword. Do you think that I cannot appeal to my Father, and he will at once send me more than twelve legions of angels? But how then would the scriptures be fulfilled, which say it must happen in this way?” At that hour Jesus said to the crowds, “Have you come out with swords and clubs to arrest me as though I were a bandit? Day after day I sat in the temple teaching, and you did not arrest me. But all this has taken place, so that the scriptures of the prophets may be fulfilled.” Then all the disciples deserted him and fled.

Those who had arrested Jesus took him to Caiaphas the high priest, in whose house the scribes and the elders had gathered. But Peter was following him at a distance, as far as the courtyard of the high priest; and going inside, he sat with the guards in order to see how this would end. Now the chief priests and the whole council were looking for false testimony against Jesus so that they might put him to death, but they found none, though many false witnesses came forward. At last two came forward and said, “This fellow said, ‘I am able to destroy the temple of God and to build it in three days.’” The high priest stood up and said, “Have you no answer? What is it that they testify against you?” But Jesus was silent. Then the high priest said to him, “I put you under oath before the living God, tell us if you are the Messiah, the Son of God.” Jesus said to him, “You have said so. But I tell you, From now on you will see the Son of Man seated at the right hand of Power and coming on the clouds of heaven.” Then the high priest tore his clothes and said, “He has blasphemed! Why do we still need witnesses? You have now heard his blasphemy. What is your verdict?” They answered, “He deserves death.” Then they spat in his face and struck him; and some slapped him, saying, “Prophesy to us, you Messiah! Who is it that struck you?”

Now Peter was sitting outside in the courtyard. A servant-girl came to him and said, “You also were with Jesus the Galilean.” But he denied it before all of them, saying, “I do not know what you are talking about.” When he went out to the porch, another servant-girl saw him, and she said to the bystanders, “This man was with Jesus of Nazareth.” Again he denied it with an oath, “I do not know the man.” After a little while the bystanders came up and said to Peter, “Certainly you are also one of them, for your accent betrays you.” Then he began to curse, and he swore an oath, “I do not know the man!” At that moment the cock crowed. Then Peter remembered what Jesus had said: “Before the cock crows, you will deny me three times.” And he went out and wept bitterly.”

Notes

[1] Peter Rollins, The Fidelity of Betrayal, Paraclete Press, 2008, pp. 1-3.

[2] Ibid., p 29.

[3] Ibid., p. 21, quoting Slavoj Žižek, The Puppet and the Dwarf (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), 16 (italics in original).

The Wilderness of Death and Loss

March 29, 2020

Part 5 of the series “A Journey through the Wilderness“

Ezekiel 37:1–14; John 11:1–45

The shop owner denies that the parrot is dead, insisting merely that he is resting. He adds that the parrot—a “Norwegian Blue”—is likely just “pining for the fjords.”

The customer objects: “What kind of talk is that?, look, why did he fall flat on his back the moment I got ’im home?” and the shop owner insists that the Norwegian Blue prefers keeping on its back. When the customer points out that the only reason that it had been sitting on its perch in the first place was that it had been nailed there, the shop owner insists that this was necessary to prevent the bird from breaking apart the bars and escaping.

The customer responds that the bird is “demised” and when the shop owner insists the bird is once again “pining for the fjords” the customer says:

Mr. Praline : It’s not pinin,’ it’s passed on! This parrot is no more! It has ceased to be! It’s expired and gone to meet its maker! This is a late parrot! It’s a stiff! Bereft of life, it rests in peace! If you hadn’t nailed him to the perch he would be pushing up the daisies! Its metabolical processes are of interest only to historians! It’s hopped the twig! It’s shuffled off this mortal coil! It’s run down the curtain and joined the choir invisible! This…. is an EX-PARROT!

What I like about this sketch is not only that it’s funny, but that it reveals a real truth about our culture. We don’t like to talk about death directly. John Cleese’s little rant at the end is wonderful because of the number of euphemisms he employs to say “is dead.” He could have added a few more:

Kicked the bucket, gone to his great reward, crossed over, bought the farm, departed, deceased, late, lost, no longer with us, gave up the ghost, expired, in a better place, gone home, transitioned (that’s a new one I recently encountered), or the most common one: passed away.

Now, of course, it is not only death which we have euphemisms for. There are all kinds of things that we don’t talk about directly—sex, bodily functions, etc.—but it seems that we have special difficulty speaking about death.

Do we imagine that if we don’t mention it, it won’t happen? Do we pretend that the death will not come to us if we just ignore death? Why is it so hard for us to say, “So and so died”?

II. SPEAKING DIRECTLY

Speaking directly wasn’t a problem for the authors of the Hebrew Bible. There are passages from Genesis that make that clear:

Thus all the days that Adam lived were nine hundred thirty years; and he died….

Thus all the days of Seth were nine hundred twelve years; and he died….

Thus all the days of Enosh were nine hundred five years; and he died.

Genesis 5

Part of that directness, of course, comes from what the ancient Israelites believed. The most ancient Israelite understanding did not contain a belief in any kind of life after death. A lifetime was all one was due. You lived your life, and at the end you went down to the grave. You died. Some versions had a shadowy afterlife known as Sheol, but it was nothing like real life. Life was in the here and now. And so, perhaps, it was easier for them to speak directly about death—it was everywhere around them.

Much the way it was around us a couple generations ago. It used to be the case that when people died, they died at home. Their bodies were cleaned and cared for by the family, before the corpse was taken away by the undertaker so that after the funeral, it would be buried in a coffin in a grave at the graveyard. Now, people die in hospitals. When they die, the family is whisked out of the room. Hospital staff prepare the body, and then the body is transported to the funeral director who places the loved one into a casket so that after the memorial service it can be interred into a plot at the memorial garden. Why it’s almost like no one has died.

Our removal from daily contact with death has removed our ability to talk about death honestly. And that is something that we need to do.

III. DEATH AND THE WILDERNESS

Of all the wilderness experiences we’ve been looking at, death and loss are perhaps the most difficult to face. Want, fear, despair, and tragedy all place us in wilderness experiences but none seems more profound than the wilderness of death.

Each of the other experiences admits of having a reversal: if we want for something, we might get it; if we fear, we might be encouraged; if we despair, we might find hope, and when we face tragedy, we might find rescue. But death is a particular one. Death is irreversible. The child of a friend of mine asked her after their family dog had died, “When the dog is done dying, will he come back?” What children fail to grasp, we grasp all too well: death is final. When we find ourselves in the wilderness of death and loss, we do not console ourselves with the possibility that the one we mourn might return to life soon.

This may be why we’re so reluctant in our contemporary culture to name death directly. It’s why we—not just disgruntled parrot purchasers—have come up with so many euphemisms for it. Perhaps if we ignore it, it can’t really hurt us. And perhaps, it’s a way of avoiding the term because it has so much power.

There’s a reason why the ancient community of Israel around the time of the Babylonian Exile was portrayed metaphorically as a valley of dry bones. The image of death and utter ruin was how the Israelites were feeling as their nation was conquered, their kings’ line ended, their temple destroyed. Ezekiel speaks to a nation in exile and to capture the feelings of the people of Judah, uses imagery of death, destruction, and loss. Of dry bones—an image of a long-ago lost battle that brought utter devastation.

In the Gospel lesson, too, we encounter death. Jesus has come to Bethany, modern-day Al-Azariah, where his friend Lazarus has died. Lazarus’ sisters Mary and Martha had entreated Jesus to come earlier to heal the ailing man, but by the time he arrived, Lazarus had been dead for four days.

When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. He said, “Where have you laid him?” They said to him, “Lord, come and see.” Jesus began to weep. So the Jews said, “See how he loved him!” But some of them said, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?”

This is an extraordinary paragraph. It describes Jesus as “greatly disturbed in spirit” and “deeply moved” and that he began to weep. These are extraordinary statements given that generally throughout John’s gospel Jesus isn’t fazed by much. He’s always in control. In fact, he’s more composed while he’s being crucified than he is here facing the death of a dear friend.

Even for John’s always in control Jesus, death and loss are an overwhelmingly powerful wilderness experience.

But it is not a wilderness that can be faced with anything but honesty and directness.

IV. GRIEF IN THE WILDERNESS

And we need it to assist in our grieving.

We as a community, as a nation, and as a world find ourselves in a wilderness experience that we haven’t been in in nearly a century. We are in the midst of a global pandemic, in which an entirely new virus is wreaking havoc on our healthcare system and our way of life. The projections of deaths caused by this virus range from the tens of thousands—if we’re lucky and do all the right things—to the millions if our healthcare system is overwhelmed.

Right now, a lot of people are going through tremendous amount of anxiety about the state of the economy, loss of jobs, access to resources. But behind it all looms the specter of tremendous loss of life. Quite simply, we have seen that the threat of death for so many has motivated us toward extraordinary steps of solidarity and self-sacrifice.

But in order to face this challenge, in order to face our grief, we need to be able to name what it is we grieve.

I submit to you that it is at times like this that talking around the issue does no good at all. Part of any grieving process is in coming to terms with the object of our grief. The first step toward healing and wholeness is in facing the reality of our circumstances head on.

That is why it is so important to avoid all the trite sentimentality that hides the reality of death. In our own desire to avoid causing harm to others, we engage in platitudes like “they’re in a better place” or “they’re smiling down on us” or other things that are seemingly designed to distract us from the pain.

If any of you is at my funeral, please don’t say, or let anyone else say, anything like, “I’m sure he’s in a much better place now” or “I’m sure he’s smiling down at us” or anything like that. Please just say—if you feel the need to say anything—“Mark Schaefer is dead.” I would consider it a personal favor.

Sometimes, our inability to be honest about death borders on the absurd. I saw an announcement once about a memorial for September 11th and they referred to an opportunity for those who “passed away” on September 11, 2001. Folks, given the number of people who were killed or murdered on that day, it is almost disrespectful to their memory to say that they “passed away”—as if it were a slow fade to black. If we are committed to justice, neither the murdered dead of September 11th, nor the murdered millions of the Holocaust, or the murdered million of the Rwandan genocide or the Congolese civil war, can be referred to as having “passed away.” Nor can we say that about those who die from famine and disease. From the scourge of poverty. Of those—for reasons of justice—we cannot say “They passed away.” Nor can we simply say “They’re in a better place now.” If hundreds of thousands or millions should die from the coronavirus because we were not willing to take the steps we needed to to protect against such loss of life, trite sentiment will not excuse our inaction or our recklessness. Our sense of justice won’t allow it. Those multitudes were killed or they died. And the injustices that lead to those deaths are not accounted for by the idea of death as a release.

In the spring of 2000, a friend of mine was murdered. She was stabbed to death by her neighbor who wanted her car to drive to a party. It was a brutal, senseless crime that snuffed out the life of a talented and well-liked individual. On the drive to the funeral, one of the people in the car remarked, “It’s good that they’re calling it a memorial service, not a funeral. That way we can celebrate, because it’s only the body that is dead—the important part still lives on.” I was apoplectic. If the ‘important part’ still lived on, why be sad? More importantly, why be outraged at our friend’s murder?

Not to speak honestly about death would be an injustice, and hardly a fitting remembrance for my poor murdered friend Alison.

V. THE WILDERNESS OF DEATH AND THE PROMISED LAND OF RESURRECTION

But there is another, deeper reason we need to be honest about death. We need to be honest about death if we are to keep our faith from being nonsensical. We need to be honest about death if we are truly going to appreciate the power of the resurrection.

As I noted before, in Ancient Israel, there was not a real belief in life after death. By Jesus’ day, many Jews believed that on the last day, with the coming of the Messiah and the inauguration of the Reign of God, that the dead would be raised to new life—they would be resurrected. But belief in the resurrection did not imply that death was any less real. Belief that one day God would raise the dead to new life did not lessen their appreciation of death. Indeed, their faith was defined by the reality of death. As is ours.

Because we Christians do not believe that Jesus “passed away” on the cross. Jesus died. A real death. In the words of the ancient creed, “He descended into hell”—a way of saying, he descended into the realm of the dead—he was among the dead. I had heard from a number of others that the Board of Ordained Ministry liked to ask its ordination candidates “Where was Jesus on the Saturday between Good Friday and Easter Sunday?” They never asked me that question. I kind of wish they had, because I was ready with the answer: he was dead. His life, his being, his existence was cut off.

Jews did not believe in a separation of body and soul. That was a Greek idea. Jews believed that human beings were psychosomatic wholes—body and soul were one. There was no way to get around death. You couldn’t euphemize your way out of it. You couldn’t say, “Well, the important part still lives on.” You couldn’t say, “It’s okay, Peter, I’m sure Jesus is in a better place”. All you could say was “Jesus is dead.”

German theologian Jürgen Moltmann writes that when Jesus died on the cross, it was not the death of the human Jesus only, but a death of the divine Son of God. That is, Christians believe that the Son of God—one of the persons of the Trinity, one of the community of God’s innermost being—became flesh and dwelled among us as the human being Jesus of Nazareth. Some throughout history have supposed that when Jesus was crucified, only the human being Jesus died.

Moltmann says that when Christ was crucified, it was not only the human Jesus who died, but the divine Son. There was a death within God’s innermost being. That God knew death within Godself. That God took death into God’s very being and suffered that death within. And that for God that death was not any less real than any death that we experience. The absence, the loss, the pain.

But we all know the story does not end there. We know that on the third day, God raised Christ from the dead. Not just the divine Son, but the human Jesus. A restoration to bodily existence. A stunning reversal from the fortunes of death. The addition of sinews and flesh to the valley of dry bones and even the raising of Lazarus from the dead (since we assume he died again at some point) can only begin to prefigure the stunning nature of the resurrection and the defeat of death itself.

But it is only in contemplation of the awesomeness, the mystery of death, that we truly understand the power of resurrection. It is not something that happens naturally. It is not the same thing as our spirits flying off to some other parallel dimension or plane. It is not the same thing as immortality. It is not really even life after death. It is life out of death. That out of the midst of death, life emerges. New life. Resurrected life.

This is the hope that Paul refers to when he says that we do not “grieve as others do who have no hope…” He is not promising that we will not grieve—only that we will not grieve in the same way that others do, but that we grieve with hope. As Paul would say to the Corinthians, Jesus is the “first fruits” of those who have died. His resurrection is not an isolated incident, but that we, too, will all see Resurrection together—and this is our hope.

VI. END

It is with that hope, then, that we are able to face death. Not as something to be talked around. Not as something to be glossed over. Not as something that has lost its power. But as something real, something true, something powerful, that nevertheless is not the final word.

We all here will die. The death rate will remain the same: one per person. But we can face death without fear. We can face death with hope. Because we know that God has not given death the final word—love has the final word. Death is not in control of this world, God is. Death may be our destiny, but it is not our eternal fate: resurrection is.

We may find ourselves in a wilderness of death and loss. We may find ourselves in a time of grief and sorrow. We presently find ourselves in a time of great anxiety where we worry about those we love and fear the death toll that could come.

But here in this wilderness, God too is found. The God who knows death in God’s very own being. The God who is not removed from our suffering and death, but is in the midst of it. And the God who through his apostle has promised us that nothing, not even death, can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus.

The texts

Ezekiel 37:1–14 • The hand of the Lord came upon me, and he brought me out by the spirit of the Lord and set me down in the middle of a valley; it was full of bones. He led me all around them; there were very many lying in the valley, and they were very dry. He said to me, “Mortal, can these bones live?” I answered, “O Lord God, you know.” Then he said to me, “Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the Lord. Thus says the Lord God to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the Lord.”

So I prophesied as I had been commanded; and as I prophesied, suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone. I looked, and there were sinews on them, and flesh had come upon them, and skin had covered them; but there was no breath in them. Then he said to me, “Prophesy to the breath, prophesy, mortal, and say to the breath: Thus says the Lord God: Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live.” I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood on their feet, a vast multitude.

Then he said to me, “Mortal, these bones are the whole house of Israel. They say, ‘Our bones are dried up, and our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.’ Therefore prophesy, and say to them, Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. And you shall know that I am the Lord, when I open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people. I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the Lord, have spoken and will act,” says the Lord.

John 11:1–45 • Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha. Mary was the one who anointed the Lord with perfume and wiped his feet with her hair; her brother Lazarus was ill. So the sisters sent a message to Jesus, “Lord, he whom you love is ill.” But when Jesus heard it, he said, “This illness does not lead to death; rather it is for God’s glory, so that the Son of God may be glorified through it.” Accordingly, though Jesus loved Martha and her sister and Lazarus, after having heard that Lazarus was ill, he stayed two days longer in the place where he was.

Then after this he said to the disciples, “Let us go to Judea again.” The disciples said to him, “Rabbi, the Judeans were just now trying to stone you, and are you going there again?” Jesus answered, “Are there not twelve hours of daylight? Those who walk during the day do not stumble, because they see the light of this world. But those who walk at night stumble, because the light is not in them.” After saying this, he told them, “Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I am going there to awaken him.” The disciples said to him, “Lord, if he has fallen asleep, he will be all right.” Jesus, however, had been speaking about his death, but they thought that he was referring merely to sleep. Then Jesus told them plainly, “Lazarus is dead. For your sake I am glad I was not there, so that you may believe. But let us go to him.” Thomas, who was called the Twin, said to his fellow disciples, “Let us also go, that we may die with him.”

When Jesus arrived, he found that Lazarus had already been in the tomb four days. Now Bethany was near Jerusalem, some two miles away, and many of the Judeans had come to Martha and Mary to console them about their brother. When Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went and met him, while Mary stayed at home. Martha said to Jesus, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. But even now I know that God will give you whatever you ask of him.” Jesus said to her, “Your brother will rise again.” Martha said to him, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.” Jesus said to her, “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him, “Yes, Lord, I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.”

When she had said this, she went back and called her sister Mary, and told her privately, “The Teacher is here and is calling for you.” And when she heard it, she got up quickly and went to him. Now Jesus had not yet come to the village, but was still at the place where Martha had met him. The Judeans who were with her in the house, consoling her, saw Mary get up quickly and go out. They followed her because they thought that she was going to the tomb to weep there. When Mary came where Jesus was and saw him, she knelt at his feet and said to him, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died.” When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Judeans who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved. He said, “Where have you laid him?” They said to him, “Lord, come and see.” Jesus began to weep. So the Judeans said, “See how he loved him!” But some of them said, “Could not he who opened the eyes of the blind man have kept this man from dying?”

Then Jesus, again greatly disturbed, came to the tomb. It was a cave, and a stone was lying against it. Jesus said, “Take away the stone.” Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, “Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead four days.” Jesus said to her, “Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?” So they took away the stone. And Jesus looked upward and said, “Father, I thank you for having heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.” When he had said this, he cried with a loud voice, “Lazarus, come out!” The dead man came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, “Unbind him, and let him go.”

Many of the Judeans therefore, who had come with Mary and had seen what Jesus did, believed in him.

The Wilderness of Tragedy

Rev. Mark Schaefer

March 22, 2020—Lent IV

Part 4 of the series “A Journey Through the Wilderness”

1 Samuel 16:1–13; John 9:1–41

I. BEGINNING

I’m one of those people who actually thinks that Lee Harvey Oswald killed President John Kennedy and acted alone. There are a great many people who feel otherwise and who believe that a vast conspiracy, perhaps the CIA, perhaps the Russians, perhaps the mob, or the Cubans, put together an operation to bring down the 35th president.

Conspiracy theories often circulate after major tragedies. The AIDS crisis. The Challenger explosion. The 9/11 attacks. The Sandy Hook shooting. The Notre Dame fire. You name it, there’s been a conspiracy theory designed to explain it.

No doubt you have heard conspiracy theories about the coronavirus involving the North Korean secret police or the Democratic Party. Every tragedy seems to bring out the conspiracy theories. Sometimes, they’re put out by people who are trying to exploit the tragedy to sow confusion. Sometimes they’re put out there by people trying to troll people for a reaction. But whatever the reason that they’re put out there, people often accept them because in the face of tragedy, people are looking for explanations.

How could it be that a disaffected loner could purchase a rifle through a mail-order catalog, climb up to an upper floor of a book depository, and kill a young and dynamic president? That can’t just happen. There had to be some deeper reason, some other explanation. Things like that don’t just happen.

How could a virus leap from bats to human beings and then spread throughout the world infecting hundreds of thousands? Surely, this was someone’s plan, right? Things like this don’t just happen.

Someone must be responsible. Someone must be at fault. Someone must be to blame for this tragedy.

It is a fact of life that tragedies take place. And it is a further fact of life that the occurrence of these tragedies has profound effects on our spiritual well-being. For either we struggle to find meaning and figure out why a particular tragedy happened the way it did or we spend a fair amount of our lives anxious about tragedies that might occur. Or both.

Tragedies overwhelm us. When they occur they occupy our thinking, they dominate our news coverage. They cause us to ask all kinds of questions. Some answerable, some unanswerable. But the question we ask most is: why? Why did this tragedy happen? Why did it happen to these people? Could it have happened to me? Why did it have to happen at all?

And often we comfort ourselves by telling ourselves that there was a reason—a divine plan, perhaps—that this all happened.

Read more...

The Wilderness of Despair

Rev. Mark Schaefer

Cheltenham United Methodist Church

March 15, 2020

Part 3 in the series, “A Journey Through the Wilderness”

Exodus 17:1–7; John 4:5–42

I. BEGINNING

They say a human being can go for about three weeks without food, but can only go for about three days without water. If you’re ever in a situation in which food is in short supply you might be concerned, but were you in a situation where water is in short supply, you’d begin to despair.

Perhaps for those of us who have grown up having water as close as the kitchen tap, it’s hard to imagine what real thirst is like. It’s hard to imagine places like the Holy Land that are entirely dependent on rain for agriculture. It’s hard to imagine what it would be like, not to have water close at hand.

Jesus and the Samaritan woman.

A miniature from the 12th-century Jruchi Gospels II MSS from Georgia, 12th C

The desire for water is even greater than the desire for food. In fact, much of what we mistake for hunger is actually thirst. They say that if you’re hungry, have a glass of water. If you’re still hungry ten minutes later, then eat.

Water gives us not only our food, it gives us our life. In fact, life itself would not be possible without water. We’re about two-thirds water ourselves. The surface of our planet is 70% water.

People like living near water and vacationing near water: on lakes, on rivers, at the ocean. There’s something comforting about having water nearby, almost as if we recognize that deep primal need to satisfy our thirst. I always have water nearby whenever I step into the pulpit to preach. Whether I ever actually get dry mouth or not, whether I ever actually need it, it is a comfort for me to know it’s there.

Because when water is not around, circumstances are dire. And we can despair.

Read more...